This article originally appeared in The Washington Post

Sometimes, a shift in perspective makes all the difference. I am 100 feet deep in a Bahamian sea, finning along a reef wall that plunges like a waterfall of color into the blue depths below. Jacks, parrotfish and dugongs glide through a jungle of corals and sponges — green, yellow, purple, red — that sprout from the reef. A school of Bermuda chub passes overhead, silhouetted in the refracted sunlight. And here, at the nadir of this dive, my mood is improving by the second.

I’m a half-mile offshore of Cat Island a crooked scythe of limestone 130 miles and a galaxy away from the cruise ports, casinos and bulging resorts of Nassau and Freeport. Cat is one of the Out Islands of the Bahamas, an assortment of wispy islets strewn like twigs across the tropical Atlantic Ocean.

I had arrived the prior night on a 33-seat prop plane from Nassau, exhausted and irritable from sleep deprivation and a roster of vain stresses. A prearranged ride took me down an unremarkable ribbon of cracked asphalt, through scrubby brush and very few signs of life, save for an open liquor store and a closed bar. Staring out the window at the unremarkable wall of green, all I could think was “Huh.”

But soon my driver, following a hand-painted wooden sign, turned down a dirt road to the Greenwood Beach Resort and I caught the first whispers of Cat Island’s allure.

“Beaches, caves, 300-year-old plantations, diving, fishing, you name it,” Donihue Waters says in a Tennessee drawl. “This island’s 50 miles long! You could spend a month here and not run out of things to do.” Waters, a repeat visitor who flies his own plane here from his home in Savannah, Ga., with his wife Angie and Kaia, their Alaskan Klee Kai, is holding court at the Greenwood’s bar. The other guests — couples from Toronto, Berlin and Houston — mill about as a safari of guitar-clutching neighbors, mostly expats with vacation homes in tiny developments nearby, wanders in for a weekly open mic night.

I don’t have a month. In fact, I barely have a long weekend and now my agenda — scuba dive, relax and repeat — suddenly sounds feeble.

No matter. I step behind the concrete-and-limestone bar to grab a Bahamian Kalik beer, dutifully recording the hit in the honor-system ledger, and head out onto the veranda to watch a tangerine moon rise over the ocean.

The Greenwood, built in the 1970s, could use an update, but it has a kitschy charm, with buoys dangling from trees, old-school chaise longues ringing a small pool and maritime relics adorning the walls of a tile-floored room used for dining, drinking, socializing and making music.

Even better, with WiFi only in that common area and no TVs on the property, guests quickly bond with each other, the three resident dogs — Luis, Nolly and Guinness — and the Greenwood’s irrepressible French managers, 34-year-old Pauline Vaz Branco and her partner, Antoine Barbier, 33.

Within minutes of arriving, I’m in a tete-a-tete with Pauline, trying to persuade her that I’m a competent diver despite the seven years that have passed since my last scuba experience. Dubious, Pauline raises an eyebrow, opens a shed packed with diving and kitesurfing gear and lays out a scuba tank, regulator and buoyancy control vest, pieces that must be assembled perfectly if one hopes to survive underwater. “Okay, we are going diving,” she says. “Show me what to do.”

The next morning, under a sunny 75-degree sky, Pauline, Antoine, the Houstonites — Clement and Caroline, who are also French — and I load our gear into a black 2005 Dodge pickup for a short drive to the boat. Like many of the Out Islands, Cat Island is a diver’s fantasy, with almost no competition for dozens of dive sites along a reef-laced windward coast and not another viable speck of land to the east until Africa.

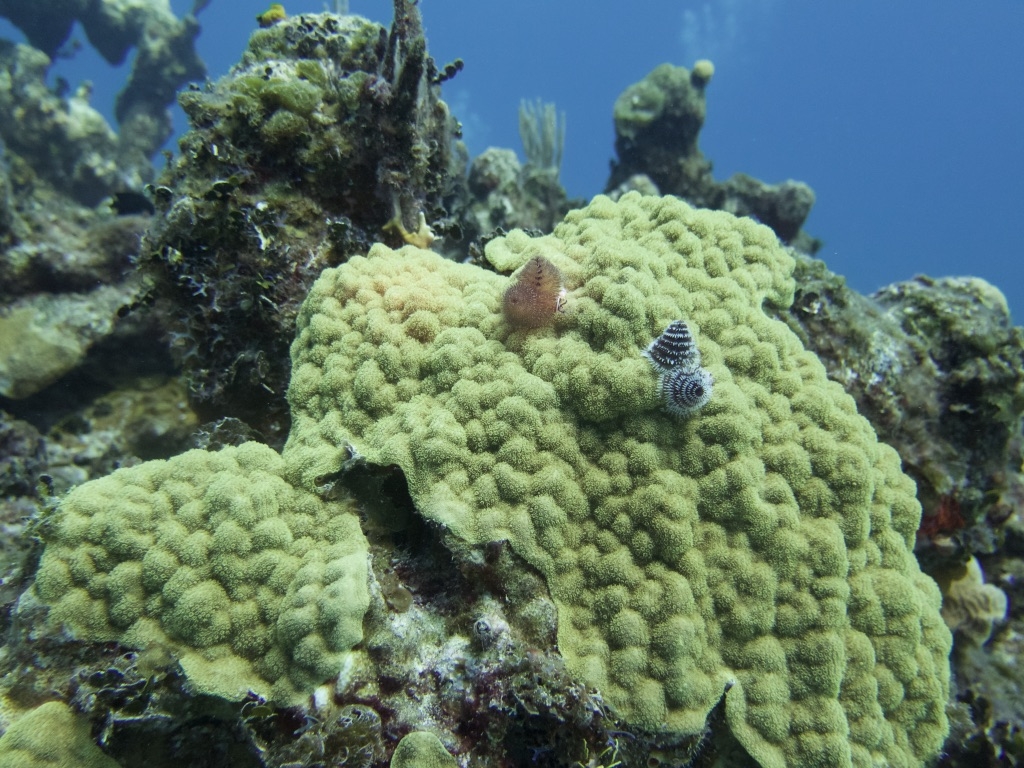

We wade our gear out to the boat, a 26-foot Mako, weigh anchor and motor off to the dive site. The only divers are Pauline, Caroline and myself. We drop to 40 feet and start following the descending contours of the reef. Like many divers, I bide too much time scanning for megafauna, but Pauline knows that the soul of the reef, as in much of life, lies in the details. She uses a flashlight to point out small fascinations I never would’ve seen on my own — a polka-dot flamingo tongue snail, poised like a rare gemstone on a stem of coral; an arrow crab, all but completely camouflaged in a sea plume; a translucent shrimp tucked into a rocky nook.

Back aboard, Antoine steers the Mako to avoid coral heads lurking inches below the surface. The Bahamas’ shallow sand banks give these waters their mesmerizing hue, an effect that led Spanish explorers to dub these islands baja mar (low seas). But contrary to the familiar discovery fable, the Spanish weren’t the first ones here.

Cat Island was settled between A.D. 300 and 900 by Arawak Indians who sailed (or drifted) from the Lesser Antilles. Then came the Europeans, who sauntered ashore bearing gifts of subjugation and disease, a combo punch that left the entire native population dead. The Europeans left and the island sat uninhabited for 100 years.

In 1649 the English arrived, established a colony (in 1717) and, after surviving the rollicking heyday of piracy — the island is named for pirate Arthur Catt — set up cotton and sugar cane plantations powered by slaves. Alongside alluring beaches, the remnants of those manors stand today, many of them in various stages of crumbling. After England abolished slavery in 1838, many of the newly freed people began farming pineapple, tomato and other crops, building an export economy that flourished until the United States stopped buying produce from the Bahamas in the 1940s because too much of the crop ended up rotting on the docks in Nassau. The country gained independence in 1973 but remains a voluntary member state of Britain’s Commonwealth of Nations, and English is the official language here.

A population that once numbered 5,000 has dropped to 1,300, forcing the recent closure of one of the island’s two schools and its orphanage. But there are hints that tourism could kindle a revival: A trio of small airlines are boosting service to the island’s main northern settlement, Arthur’s Town, and one French expat I met is building luxury rental homes that will rent for $10,000 a week — personal chef and other extravagances included.

Poking around on Cat Island’s southern end, I find some action. On Saturday night, Donihue and Angie invite me along for a 25-minute drive to the island’s cultural district, known as the Fish Fry, a string of tiny streetfront bars, restaurants and shops along the west coast.

At a pastel-yellow shack called Anniboo, five guys in jeans and island-style shirts sit at the open-air bar intently watching a Golden State Warriors-Sacramento Kings game on TV. We order Kaliks and a plate of conch fritters, paying with U.S. dollars and taking change in equal-value Bahamian dollars, as one of the guys explains the high interest: Kings guard Buddy Hield is one of two Bahamians in the NBA, along with the Phoenix Suns’ 7-foot-1 center Deandre Ayton.

They aren’t in the mood to chat, so I follow a sand path behind the shack to a gorgeous beach, where moonlight shimmers across Exuma Sound. Gazing down this Elysian coast with no other artificial light visible, I realize how few places like this remain — peaceful, simple communities, anchored on the shoals of paradise.

The next day, I join the Berliners, Daniela and Mark, in their rental car, which they had acquired from a local without showing identification or a credit card, or even filling out a form. After snorkeling a deserted limestone cove, we follow a road that rises toward Cat Island’s most prominent hill. At the head of a small parking area, we start up a trail flanked by painstakingly hand-carved Stations of the Cross. A short, steep walk beyond the stone Station VIII — “Weep not for me but for yourselves and your children” — delivers us to the highest point in the Bahamas, 206 breezy feet above sea level.

But it’s not the 360-degree views that hold our attention. It’s the (sort of) mash-up of miniaturized medieval castle and a church, complete with a tiny chapel, elf-sized passageways, wood-plank bed and bell tower. A hermitage, it turns out, built in 1939 by Monsignor John Hawes, an English priest and architect who named the hill Mount Alvernia, after La Verna, a Tuscan hill bequeathed to Saint Francis of Assisi as a place for private contemplation. Hawes intended to similarly hole up on Alvernia but ultimately couldn’t abide his own plan: He continued building churches throughout the Bahamas until his death in 1956.

As with most places I go on Cat Island, we have the hermitage grounds to ourselves and encounter no guardrails, restrictive signage or other people. I’m sure there are rules here but the overarching vibe is that people do pretty much what they want while finding a way to get along with everybody else.

That aura is in play back at the Fish Fry, where we sit down at CeeDee’s Restaurant and Bar (still bearing it’s former name, Sunshine Restaurant) as the matron is writing the menu on a whiteboard. Lobster. Conch. Barbecued ribs. All local. A Santa-sized Bahamian man with a white beard appears, clad in khaki shorts, blue T-shirt and black beret, clutching half a flask of Absolut vodka.

I ask if fresh fish is on the menu.

“Oh, we got the grouper,” he says.

“We ain’t got no grouper!” the woman corrects him.

“Oh, then the barracuda.”

“No barracuda, either.”

“We got red snapper.”

“No, we don’t! Stop selling these people fish we don’t have.”

Pompey Johnson, who says he’s “70-plenty years old . . . and the best accordion player in the world,” takes a seat and continues.

“In 1952, when King George died, we marched down this road here.” He points a few feet from where we’re sitting. “Marched all day because we respect the queen.” Pompey pauses. “Did you know I fought in the Bay of Pigs? And played my music at the Smithsonian?”

I don’t know what to believe but I want to hear some accordion, so I press him. Pompey drives off with a friend and returns 10 minutes later with a circa-1960 red Hohner Erica squeezebox and leans into polka tunes and waltzes while a boy of about 6 plays irrelevantly on an oilcan goatskin drum.

Pompey tries to get bandmate Cedell Hunter to stop cooking long enough to play rake-and-scrape — traditional Bahamian music featuring a scraped saw, drum and melody instrument such as an accordion or guitar. Someone even produces a stage-ready saw. The music never happens, but when I return to the District, I Google his band, Bo-Hog & Da Rooters, and sure enough, there’s Pompey, squeezing away on a Smithsonian Folkways recording.

En route back to Greenwood, we digress to the island’s southern coast, pulling up to Da Pink Chicken, a sky-blue, concrete-and-plywood bar overlooking a channel where the tide is pushing into a lagoon. On a dock, two Bahamians use a hatchet to crack open conchs and toss the shells onto a mountainous pile. Adjacent to an outdoor kitchen where a woman is grilling conch, a crowd of 15 — many from the expat crew I met at the Greenwood open mic — swill beers and spin tales as a lipstick sunset lights up water and sky.

On my last morning, I wake just after dawn and kayak over a still sea to where small waves are curling over a reef, their white foam dazzling in the early sun. Below me, fish dart around green domes of coral. To my left, a deserted beach arcs toward infinity. Back at Greenwood, people appear on shore. But the sea is calling, and I’m not going back just yet.

Comments